- Have any questions? Contact us!

- info@dr-rath-foundation.org

Progress in Cellular Health Science: An End-Of-Year Message from Dr. Matthias Rath

December 23, 2016

Hospital Food And Nutrition Classes In Medical Schools: Can You Work Out What The Connection Is?

January 12, 2017Giordano Bruno – martyred for being years ahead of his scientific contemporaries

It is proof of a base and low mind for one to wish to think with the masses or majority, merely because the majority is the majority. Truth does not change because it is or is not believed by a majority of the people.

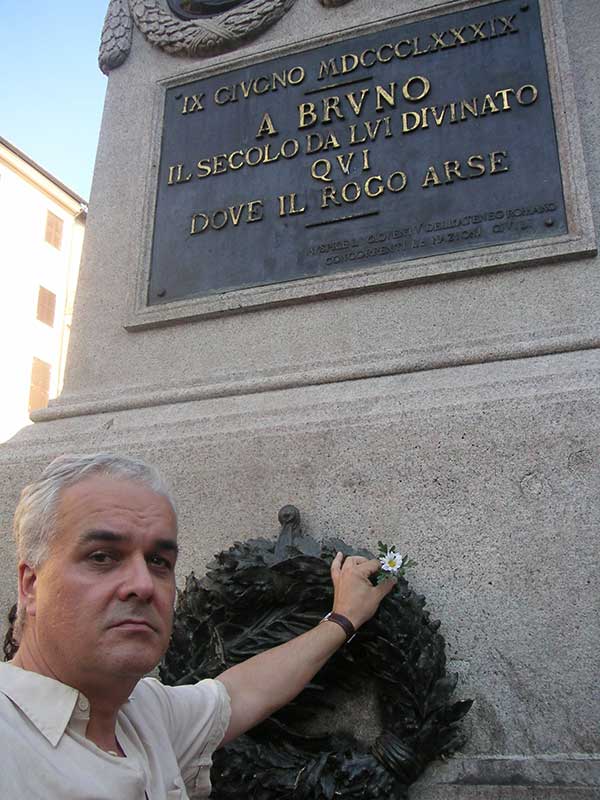

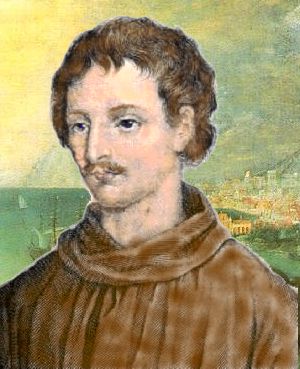

On the morning of Thursday 17th February, 1600, Giordano Bruno, an Italian philosopher, priest, and cosmologist, was burned to death at the Piazza di Fiori in Rome. An early proponent of the idea of an infinite and homogeneous universe, it took 289 years before he was officially honored with a monument at the site of his execution. As history shows, those who make important scientific discoveries and change our perception of the world are frequently years ahead of their contemporaries.

Born in 1548 in Nola, Italy, Bruno served as a monk in Naples from the age of 15. In 1572 he was ordinated as a priest and began his religious studies at the university in Naples. As the story of his life illustrates, the more deeply Bruno studied the broader his horizons became. So much so, in fact, that in 1576 his fellow monks and supporters accused him of heresy and he fled Naples.

Bruno subsequently went via Rome and Geneva to Toulouse in France, where he stayed for more than two years and gave lectures in Philosophy at the local university.

In 1582 King Henry III became an admirer of Bruno and he subsequently served as a lecturer at the ‘College de Cambrai’ in Paris. The same year Bruno published a comedy titled ‘Il Candelaio’ (The Torchbearer), which was a great success as it openly questioned the authorities of that time – especially the Catholic Church, to whom he was increasingly becoming a serious threat.

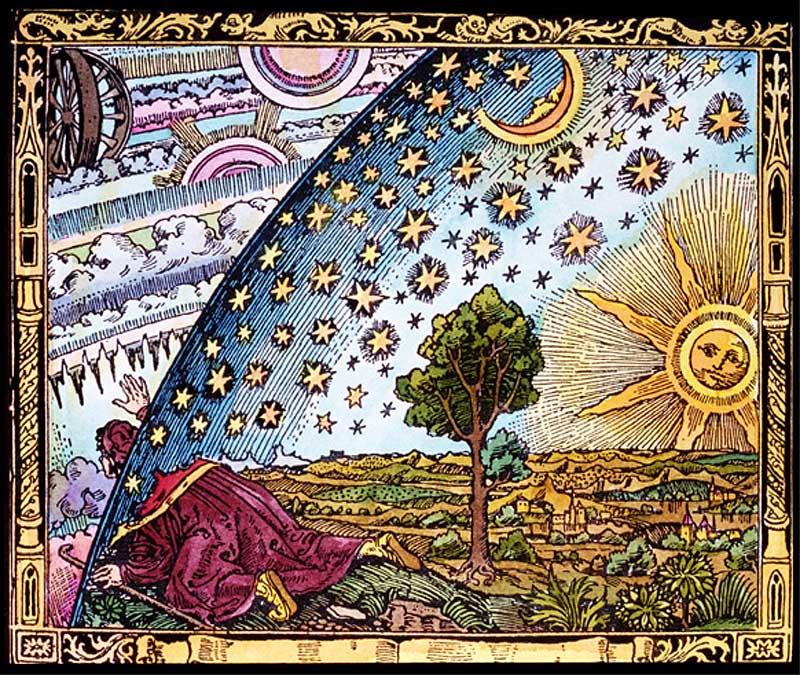

In 1583 he went to England. Here, Bruno lectured in Oxford and taught in London while writing his most significant works. These included ‘De la Causa, Principio et Uno’ (Concerning Cause, Principle and Unity; 1584); ‘De l’Infinito Universe e Mondi’ (On the Infinite Universe and Worlds; 1584); and ‘De gli heroici furori’ (The Heroic Frenzies; 1585).

The ideas in Bruno’s publications were greatly threatening to the scientific status quo. For example, in his masterpiece ‘De l’Infinito Universe e Mondi’ he extended the Copernican model (in which the Earth and other planets orbit around the Sun) and elaborated on the infinite nature of the universe and its multiple solar systems.

Of the six dialogues Bruno published in London between 1584-85, the fifth, ‘Cabala del Cavallo Pegaseo’ (The Cabala of Pegasus), was the most radical of all. In it he openly attacks the Catholic Church, Aristotle, and the skeptics. Because of his ideas, Bruno eventually had to leave England to move to Paris. Following still further academic disputes he soon left France as well, and went to Germany.

For two years Bruno found peace of mind in Wittenberg, whose people were more open to his ideas. Later he took up an invitation to travel to Helmstedt, where he stayed and lectured for a further two years.

In 1591 he received an invitation from the Venetian aristocrat Giovanni Mocenigo to relocate back to Venice in Italy. The full reasons behind Bruno’s taking up this invitation are still unknown. It’s unclear, for example, whether he was aware of the possible dangers of the Venetian Inquisition, or whether he simply wanted to make amends with the Church.

Nevertheless, events subsequently took a dramatic turn. Mocenigo, who had previously declared Bruno to be a friend, not only reported him to the authorities but also prevented him from escaping. As a result, in February 1593 Bruno was sent by the Inquisition authorities to Rome. Nevertheless, he refused to revoke his theories and held on to everything that he had been teaching. His trial lasted for seven years, throughout the entire time of which he was imprisoned.

Nevertheless, events subsequently took a dramatic turn. Mocenigo, who had previously declared Bruno to be a friend, not only reported him to the authorities but also prevented him from escaping. As a result, in February 1593 Bruno was sent by the Inquisition authorities to Rome. Nevertheless, he refused to revoke his theories and held on to everything that he had been teaching. His trial lasted for seven years, throughout the entire time of which he was imprisoned.

On 8th February, 1600, the cardinals in charge of Bruno’s trial found him guilty of heresy and he was sentenced to be burned at the stake, a common sentence for witches and heretics at that time. His response upon learning of his fate subsequently became legendary: “Perhaps you pronounce this sentence against me with greater fear than I receive it.”

Seen by some as the first scientific martyr, the story of Bruno’s life illustrates the principle that groundbreaking scientific ideas are invariably resisted by the status quo. The greater the economic interest and privileges that are enjoyed by the status quo, the more vigorous will be its resistance towards change. Far from being a mere point of history, this principle remains true to this day.

Every soul and spirit has some degree of continuity with the universal spirit, which is recognized to be located not only where the individual soul lives and perceives, but also to be spread out everywhere in its essence and substance.