- Have any questions? Contact us!

- info@dr-rath-foundation.org

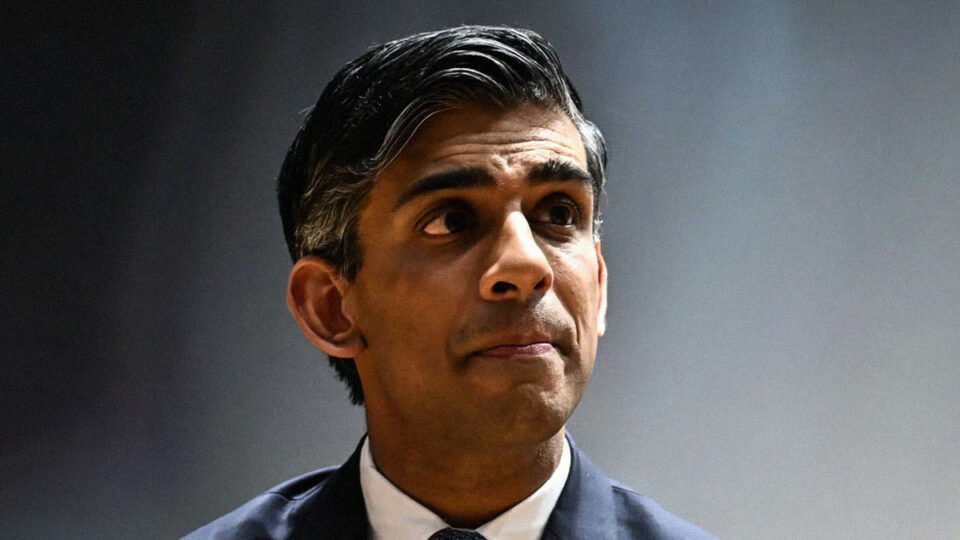

HIV/AIDS: Nobel Laureate Advocates Natural Cure

August 24, 2017

New Study Recognizes Role Of Vitamin C In Reducing Death Toll From Cardiovascular Disease

September 7, 2017A Europe for the people and by the people

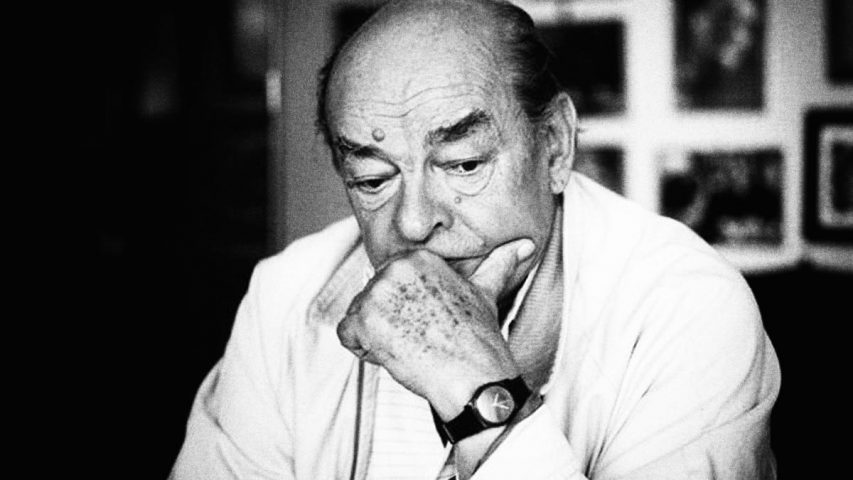

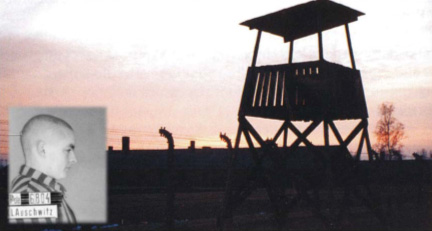

August Kowalczyk

Auschwitz prisoner No. 6804

April 2009, Kerkrade

Before I came to the podium, I looked for one word that could express everything that I feel in this moment, and I would like to begin this reflection with this word.

With the word “Thanks”. Yes, for the organizers of our seminar, it is the right word, although it is truly heartfelt, it’s a thank you for this meeting and my thank you for being here.

I looked for another word, but I couldn’t find it. I could find no better word that would include all of us.

So please excuse the familiarity; this is the right word: friends.

So, I have already met many of you, some of you have given me and my wife Eugenia your friendship, and some others of us have become friends. Today, the mutual circle of friendship is being enlarged.

It is time to introduce some of those with whom I am standing under the Flag of “A Europe for the People by the People”. And it is my deepest conviction that this has happened again thanks to the fighter, Dr Matthias Rath.

My name is August Kowalczyk; I am 88 years old, an actor and stage director who has built a reality which life has given to me, from the worst, the horrific, and the paralyzing.

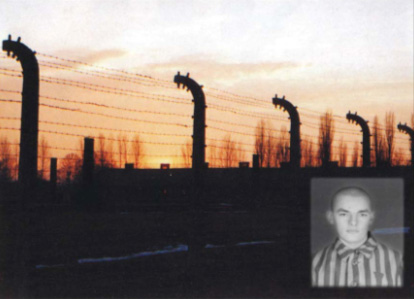

At the first brink of maturity, as an 18-year-old high school student during World War II, I was arrested and deported on the fourth of December 1940 to the concentration camp of Auschwitz, because I crossed the green border and attempted to get into France and reach the Polish army. Concentration camp number 6804.

After 18 months, receiving two death sentences and beatings (twenty-five strokes each time), I fled from the prison battalion in a mass escape. Nine of us, including me, got away, thirteen were killed, and twenty were captured.

Thanks to the Silesians, the residents of the village Bjszowy, I was saved. I stayed with them for seven weeks, and afterwards I was smuggled into the general governorate, where I became a soldier of the Polish home army.

After the war, I did my school leaving certificate, finished my academic studies and became an actor and stage director. I was an artistic director in the theatre for 17 years, and have been retired for 28 years.

| Why? Or… Why me? Or… Why exactly me? |

These three “Whys” are one question. The expected answer is intensified by the addition of a new word each time. An answer that I had to give myself immediately after the “second birth”, which means after the revolt of the prisoners in the German National Socialist concentration and extermination camp in Auschwitz that ended in a pass escape

On the 10th of June 1942, over fifty prisoners fled: thirteen were killed, twenty were captured, and nine got away.

These are my questions and my answer. But no, not immediately!

It appears that there can only be this one question: How can one live with the experience in Auschwitz?

The other question has already been asked by everyone who wants to know, how was it possible, that one human another human… yes, what…?

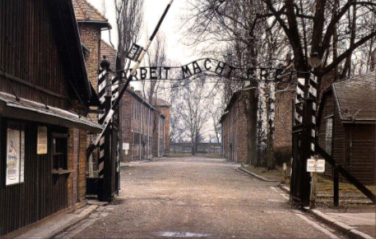

That what? That the foreman of the punishment battalion Krankenmann, a German, a prisoner, a criminal, a green corner, could erect a piece of handiwork “Arbeit macht Frei” (‘work sets you free’) on the gate, a distance of 150 metres— with a movement of his fat hip, weight 150 kilogrammes— and could break the backbones of three prisoners with a deadly blow simultaneously in five minutes; that the foreman in a very immature way was imitating, the foreman— a Pole?

That the summary Court of Justice in Katowice was a court parody, that the immediate execution, the carrying out of the sentence through shooting in the courtyard of Block 11 was no longer a joke — streams of blood ran under the fallen corpses — that Rudolf Höss, the former concentration camp commander of Auschwitz-Birkenau, who had already been in office for a long time, was called back to Auschwitz in the Spring of 1944. Special assignment: 450,000 Hungarian Jews to be liquidated in gas chambers.

Rudolf Höss successfully took care of this task as specialist in this area until the Autumn of 1941. Understanding the meaning of the term “final solution of the Jewish problem”. Everything taken care of! A specialist!

How was it possible, that…

I announced all of this. Read “Mein Kampf” (My Struggle), so said the Führer (Adolf Hitler)!

He said this and became the chancellor, according to the will of the voters.

He announced it, and the practice and life became something that a normal brain was not able to comprehend — back then and now.

The question, how is it possible, that a human…? The question is naively funny, since the very idea of the human being had been eliminated in all the calculations and summaries— as in Wannsee where 11 million European Jews became a number of the “Final Solution”.

The rest, therefore facts and the practice, were carefully prepared. Only grains of sand appeared to be innocent and they changed in the execution chambers by contact with humans, with their body warmth, and the stinking death. The uninterrupted smoking crematoriums carried the fragrance of humans that weren’t there.

A handful of ashes is all that remained of the thousands who were transported, who passed the gates in one direction only, after which were only chimneys.

Impossible… I saw it, sunken in the rhythm of my frightened heart.

Unbelievable, the words Auschwitz, Birkenau, Monowitz. Company names on the doors of the crematorium ovens are not just words, they are a “National Socialistic rite” of the conscience, of thinking, and of the German language.

Inhuman… their loving mothers were living, their families also. They all had a particularly warm heart for animals, especially dogs.

Inexpressible… the time and place was described with thousands, millions of words: Auschwitz.

On the 14th of June 2003, in the Dutch city of Den Haag, on the 63rd anniversary of the first polish transport to Auschwitz, concentration camp numbers 31 to 728, I heard simple words, and through the simplicity and evidential nature of the historical interpretation, very convincing words.

They were said by Dr Matthias Rath.

That was a meeting of human beings, who had come from almost every corner of the whole world, to strengthen Dr. Rath’s words. This meeting ended with an international appeal to the Law Court in The Hague. This appeal contained, like every appeal, postulates but it also taught. And back then somehow the umbrella of the historical truth about money, the pharma industry, and the IG Farben cartel that concealed my debtors, was knocked down, or better said perhaps not knocked down but put up. I have still not received the rightful compensation for the slave work done at the construction site of IG Farben Auschwitz from April 1941 to May 1942 to this day.

Structures that have almost always been in opposition to freedom, stood also this time on the side of the executioners not the victims. A slave is not entitled to anything. The working contract was signed by the SS, from whom the workers were delivered. In the end, the concentration camp IG Farben Monowitz came into being (Auschwitz III) in October 1942.

Under the appeal of the International Law Court in The Hague, I gave my signature: August Kowalczyk, former prisoner of the concentration camp Auschwitz-Birkenau, camp number 6804.

Since this time our mutual dealings with the program “A Europe for the People by the People” and in the interest of the Dr Rath Stiftung hospice memorial of Auschwitz, have led us to remember all the residents of Auschwitz, who offered their help and saved lives of the prisoners of the National Socialist concentration and extermination camps in Auschwitz-Birkenau between the years from 1940 to 1945.

The Dr Rath Stiftung stands at the top of the list of contributors to the voluntary builders of the hospice memorial in Auschwitz: the governments of Italy, Japan, and Switzerland.

The presence of the Dr Rath Stiftung in this European circle fills out the inexplicable absence of Berlin on the contributors’ bench. The idea which is so moving to me of the Axis of the Good would be coincidentally and so beautifully created by BERLIN-ROME-TOKYO.

All three creators of the historical axis from back then, the perpetrators of the years-long Second World War, would be found back in Auschwitz as voluntary builders for the “Good”.

Perhaps this idea would find support from the German decision-makers before the completion of the construction. While receiving my medal, the Federal Cross of Merit “Bundesverdienstkreuzes der I Klasse”, in August 2007, this seemed possible to me; it seemed to be so close that one only needed to stretch out one’s hand.

In spite of everything, I cannot imagine the founding of the hospice-memorial taking place without Berlin. That would be an inexplicable absence. And this moment — January 2010 — is not very far away — and by then it will be difficult to explain why no Germans are sitting on the bench of voluntary builders.

I will give the answer already today: the truth, its self-evidence, the understanding, friendship and trust, but above all the knowledge, are looking for each other, and I can create a mirror image of Dr Rath based on personal experiences and indeed such very subjective experiences as mine: “A Europe for the People by the People”.

We — numbers from the National Socialist concentration and extermination camps — have always believed that the face of Europe can be changed by the people. The renewal should begin at the ground level with the people, the place where we happily experienced the defeat of National Socialism. There was and is the truth about the structures created for death and money with we slaves, who not only through the SS-superhumans but also from the power-and money-obsessed human machine of IG Farben, were tested in Auschwitz.

We are the witnesses. We are the victims, who have survived. We are the commemoration of the murdered. And this memory, is our experience which needs to be shared with the young people of Europe.

The lives of the almost ninety-year-olds, whose life experiences through Nazi terrorism and then x-years of Stalin´s world concept, were changed by the eternal experience of the dependence on structures. We put up and are still putting up “legally-blessed” bans and prohibition signs. Yet, these are all illegal structures. They insult the intelligence of the people of Europe, who were… by the Nazis.

Our time is running out; we have no instruments left which can transform us, the constant customers of Europe, into a fulfilled generation. The world hears increasingly seldom our reports about hunger, poverty, slavery, genocide, murderous work, about war, hate and Nazi crimes.

From the moment of birth time is being counted. It is ever more clearly to be heard. The moment is coming in which there will be no more witnesses. When the witnesses are gone the guardians remain in your memory.

We appeal to you: they are there in the rows of the young Europeans, who have heard our testimonials, they are there under the young Japanese, who visit the museum in Shiakawa, in the monumental works of Polish artists and former camp prisoners: Jósef Szajna, number 18729, and Marian Kolodziej, number 432.

The Guardian staff of Commemorations belongs to the international chain of European schools with headquarters in Hanover, the World Peace Community with Bernim Glasman and her polish members Malgorzata Braunek and Andrej Krajewski. Also the Catholic schools in Germany, the Coalition of Youth and the Dr Rath Stiftung, which is active in Germany, Holland and in the USA. The International Fellowship Squadron in Italy, and in the end over two million Polish girls and boys who have met with me 6700 times.

That is the programme of the project called “Auschwitz Educational Society”. There are ten thousand European participants of the international competition “Humans have Prepared Humans this Destiny”. And finally the eternal testimonial, the invaluable testimonial: the museum in Auschwitz–Birkenau in Oswiecim.

We turn to you, participants of today’s meeting: do not allow this relay of remembrance to be broken. Prepare the changing layers in the fulfillment of the mission of the Guardians of remembrance.

This is a call for the relay of remembrance.

This is a call for the relay of remembrance.

A call, since the youth who hear us today, will be the last generation to experience this history. While those who are meeting whose tattooed numbers portray a legitimation to tell their history, and that of the people during the extermination, and to tell the truth. From our world today — also the truth.

We are calling for a relay of remembrance.

We are calling for a relay of life.

For a Europe for the people, by the people.

Verse not from here:

| Once, I didn’t know, That my place on earth Not in the shade of the native Linden tree, Not in the warmth of four walls, Not among those who laugh, Not with those, who are underway To love, hope, and faith, To the temples built according to their own wishes. Not in a secure country, With rocking horses, With fragrant pretzels from the market. In the end, I experienced That my place on earth Was in the middle of a crown of thorns, Worn by the posts of barbed wire, Loaded with waves Of electrical current (now not anymore, but at one time) | And therefore, Catches me, when I walk on this prickly circle, that Left…left… Gap off… Eyes right… In the camp of Auschwitz I was indeed… -and in the end, the final: I am registered, I belong to the ground. To this stones.- Then I flee from the magic of the SS-Runes From the curiosity of empty eye sockets. And yet my remembrance remains And I come back. Because I belong here, On this place On earth. |

And even from this place, which has become a dark truth about the people of the 21st century, I gather strength from my belief, that that which binds us in mutual societal health, is a programme that must be furthered with all our strength. In those days, the time of ashes, of smoke, there were human voices to be heard which were no more heard nor are heard anymore. There were also those who saved civilization from complete barbarity regardless of nationality, confession, or uniform.

When they endangered their lives to give hope in those days, or held out a helping hand, one cannot avoid seeing the social project of “Europe for the people” in practice.

At the end, I would like to remember some of them.

As I went to the camp in the morning, I took a modern cloth bag with me. That was actually foreman Bracht’s bag.

On that day, two buckets of bread and sausage pieces were standing in the “Contact box” on the floor of the shed of the commando Buna-Werke IG Farben Auschwitz. There were two cartons of calcium-filled syringes in a hiding place for medication. In those days, it was one of the few medicines that were used for tuberculosis. The syringes were to be delivered to the Polish doctor in the camp hospital. I hid the syringes in the bag and took the food.

Just at that moment I heard aggressive words behind me: “What are you doing here?”, said one of the three SS men who were on duty that day in our commando.

“Food?” He saw the bucket with foodstuffs.

“Contact with the civilians!” he called out triumphantly.

That was one of the most severe punishable offences. He wrote down my number and I didn’t come back “normally” to the camp that day.

I went as always with my third hundred?

I was arrested at the gate. I was “pulled out” by the commando. Almost two thousand colleagues walked past me and everyone saw: August got caught.

The commando was already at the camp when the SS man left the guard house. “Posener”, I called him. He came from Posen and spoke excellent Polish. He belonged to the most hard-working “food organisers” among the SS-men. And that’s why I was surprised by his sudden brutality. He pushed me through the gate and gave me a kick. He screamed something that I didn’t understand. He pushed me through the gate and gave me a kick. He screamed something that I didn’t understand.

We disappeared from the view of the watchmen at the gate behind the camp kitchen.

“I´ll take you to the bunker!”. The SS man slowed his step. “What´s the matter, August?”-

“I got caught!”-

“And I said be careful!”.

Not every SS man accepted the “organising”. We went slowly in the direction of the death blocks. There was a camp arrest underground: a bunker.

“Are any of the civilians in danger?” he asked.

“Nein!”

With an absolutely indifferent tone, but emphasising the meaning of what he was saying, he asked: “Do you have something to take care of in the block?” I looked at him over my arm. His eyes were staring at the roof of the block which we were passing.

“I have something.”

“We´re going.” He entered the block with me, let me into the room and stayed himself in the corridor.

There was complete surprise among the colleagues.

“Get rid of the bag”, I said to the room leader. “Pass out the cigarettes amongst you, the medication to the hospital in Zbyszek”. They knew for whom. I got a piece of bread for dinner and landed back in the corridor. The Posener led me silently to Block 11. The block leader of the 11th called it the ‘funktion’ prison, that was my friend Hans Musiol. And both of them led me down to the bunker: cell number 20. A dark concrete room, without a window. In the corner was a bucket. Musiol threw in a blanket. They locked the door and turned out the light. The darkness engulfed me.

I remember this incident with the Posener, because I understood first years later, that this action of the Posener’s was absolutely selfless and done with a great degree of risk. He could have met another SS man in the block, faced an unrecognisable Gestapo spy- because there were also such spies amongst the prisoners. And all of that in the name of human solidarity, that made him, an SS man, deal with me, the prisoner number 6804, there on the fields near Auschwitz, in spite of the awareness that every decision was either for life or death.

It appeared, that we decided for life. The bunker became something mutually dismal. My visit to the bunker on the way to the block was a testament to determination and the Posener´s courage. This stretched out hand was no secure act of solidarity.

A train stands at the station with an army unit that was returning from the Front on this Spring evening. The soldiers sit on the floor in the open doors of the wagons. We go along to our wagon around the front of the train at a distance of about 20 metres. Every wagon roars with the rhythm of the train stops, a witness that the trip lasts a few minutes. One hears conversations, laughs, someone plays a harmonica. The soldiers comment on our march.

An officer stands behind the backs of the soldiers who are sitting in the doors of the wagons swinging their feet. Open uniform jacket, visible medals, red-golden shoulder ribbons.

I see the officer raise his hand to his forehead and salute the prisoners walking by in a half attention position. From this impression, it seems to me as if I am unwillingly seeking the marching by.

My hundred overtakes the general’s wagon already. As it really is a general, I look back. The officer salutes even more people in prisoner clothing.

Nothing is black or white. The colored rainbow can be, for example, like the red-gold of the shoulder ribbons of the general, which was apprehended by the marching number KZ Auschwitz 6804 in the dark grey prison clothing.

Water drops fell slowly from the rotting ceiling of the cellar, and on the walls of Block Four. They ran together in thin currents, that quickened according to the nearness of the floor. Block Five was the first of the new living blocks that was opened up in December. In the cellar there was a room; the paper sacks that were laid against the wall with freshly filled straw sucked up moisture.

Under the cellar windows I shared a two-metre concrete floor with Müller, on which we now laid out the straw bag together. We carried it like a sack of potatoes. It was heavy and wet. Wooden shoes — “Dutch shoes” — wrapped up in pants, served as a pillow.

We had one blanket for two people. Half-sitting, half-leaning on the wall, we were silent, because we were afraid of words that on this unusual evening expressed hopelessness on our lips. That was Christmas Eve 1941.

The room laid out with the straw sacks was filled with the yearning and desperation of those who remembered the former Christmas Eves that had been spent in freedom. In a moment I looked at the prisoner wearing the green triangle. He came toward us to the end of the room and stopped at our straw sack.

“What´s your first name?” he spoke to me in German.

“August.”

“Do you like potato pancakes?”

My eyes certainly expressed surprise.

Müller began to laugh.

“Yes, I do.” that sounded decisive but it was tainted with a certain suspicion.

The German reached into his coat and pulled a canteen bottle out from under his arm.

“For you and your colleagues! With Christmas greetings.”

“I can´t see your shoes,” he realized suddenly.

“Wooden shoes, under the head”

“Have a nice meal. I’ll come back in a few minutes to pick up the canteen bottle.”

We shared the last potato pancake with Müller like a host wafer. He thought about his own family in Radom, and I thought about my own in Mielec and Debica.

The donator came back. He took the canteen bottle and laid a pair of boots on the roof.

“August”, may they serve you and bring you home safely and healthfully.

And he went away.

Müller looked unbelievingly after the man going away. “An angel with a green triangle,” he whispered. That was the only meeting. I never saw him again.

And the “angel” was a German, a criminal, the wearer of the green triangle, who came on Christmas Eve 1942 and gave me potato pancakes and boots and went away. He is probably in his own “heaven”, as he carried it within himself.