- Have any questions? Contact us!

- info@dr-rath-foundation.org

Assumed safety of pesticide use is false, says top government scientist

September 28, 2017

Prostate cancer on the rise in rural India, cases may double by 2020

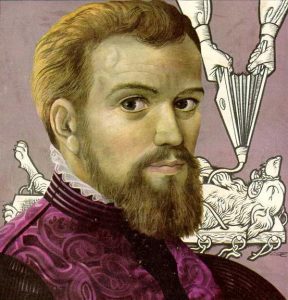

October 1, 2017Andreas Vesalius – A Revolutionary In The Field Of Human Anatomy

In the field of human anatomy, the discoveries of Andreas Vesalius were profound. So important was his impact on this scientific discipline that he is often referred to as its founding father. But as a result of overturning centuries of established medical dogma and methodically proving it to be wrong, he suffered years of struggle against the authorities of the time and was publicly discredited.

Andreas Vesalius

Andreas Vesalius was born in 1514 in Brussels. His family included a number of physicians and pharmacists. Wealthy and well-educated, the family supported the young Andreas and sent him to some of the best schools of the time.

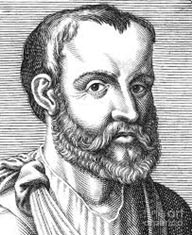

As a young man, Vesalius studied medicine in Paris, Louvain and Padua. At that time the field of medicine was strongly influenced by the work of the Greek physician Galen, who for 1300 years had been widely considered to be the ‘father of medical knowledge’.

Upon receiving his medical doctorate at the University of Padua in 1537, Vesalius was immediately offered its chair of surgery and anatomy. He went on to became a famous professor of anatomy and physician.

Challenging the ideas of Galen

Galen

In 1539, when a Paduan judge became interested in his work and made bodies of executed criminals available to him, Vesalius’ supply of human dissection material significantly increased. This enabled him to make important scientific discoveries. For instance, he was able to demonstrate that men and women have an equal number of ribs. Until then, it had been common belief that men had one less rib than women.

Vesalius also disproved the assumption of Galen (who he discovered had only carried out dissections of animals) that humans and apes share the same anatomy. Contrary to Galen’s observation that the sternum of the ape consisted of seven parts, Vesalius discovered that the human sternum had only three parts.

Vesalius went on to make significant discoveries relating to practically all of the body’s systems, including the cardiovascular and nervous systems. His studies of the vascular and circulatory systems made an important contribution to the understanding that the heart acts as a pump to move blood around the body.

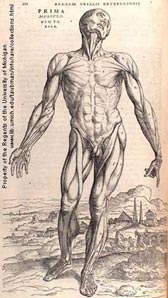

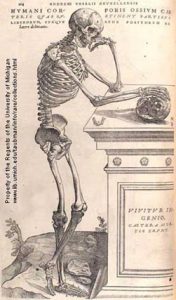

In 1543 Vesalius published a set of seven books, De humani corporis fabrica libri septem (“On the fabric of the human body in seven books”). A major advance in the history of anatomy, they went on to become the most influential publications in the entire history of the discipline. Containing carefully drawn images of the human body shown standing, stripped of skin, in outdoor scenes, their provocative style contributed to the ongoing harassment Vesalius received at the hands of the conservative Catholic Church.

But Vesalius also had admirers. Emperor Charles V was impressed by his books and made him Imperial physician at his court. After the abdication of Charles V, Vesalius continued to find great favor with his son, Philip II, who gave him a pension and title.

But Vesalius also had admirers. Emperor Charles V was impressed by his books and made him Imperial physician at his court. After the abdication of Charles V, Vesalius continued to find great favor with his son, Philip II, who gave him a pension and title.

Among conservative physicians, however, Vesalius’ work was publicly discredited and he was attacked on a regular basis. As a result, persecution and controversy accompanied him right up until the end of his life. Vesalius died in Zakynthos, Greece, in 1564. Aged only 49, he is said to have been in such debt that a benefactor had to pay for his funeral.

Tellingly, however, in a sign of how influential and enduring the work of Vesalius proved to be, just over 300 years after De humani corporis fabrica libri septem had rid the medical world of its blind obedience to the ideas of Galen, Charles Darwin used its vast stock of anatomical knowledge to build his famous ‘theory of evolution’.

In applying a methodical scientific approach to the study of anatomy, Vesalius was clearly way ahead of his time. But the story of his life also reminds us that, in reaching for and discovering new paths, innovators in the fields of science and medicine are invariably attacked and discredited by the authorities of their time – a tactic that continues to be used against scientific visionaries to this very day.