- Have any questions? Contact us!

- info@dr-rath-foundation.org

Widely used blood pressure drug linked to ‘substantially increased risk’ of skin cancer

December 7, 2017

Inauguration of ‘The Little Vitamin Club’ in Świdnica, Poland

December 22, 2017Mahatma Gandhi: Achieving Liberation From Oppression Through Non-Violent Resistance

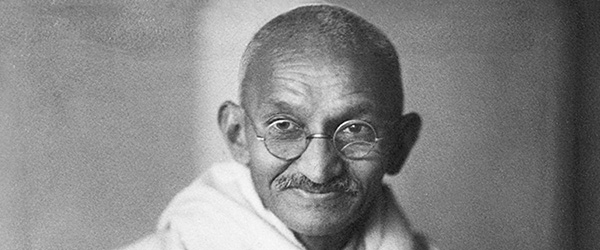

Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi’s non-violent philosophy led his followers to name him ‘Mahatma’, which means ‘the one with the great soul.’ Born in India in 1869, Gandhi became the most prominent leader in India’s long struggle for independence from the colonialist rule of Great Britain.

Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi’s non-violent philosophy led his followers to name him ‘Mahatma’, which means ‘the one with the great soul.’ Born in India in 1869, Gandhi became the most prominent leader in India’s long struggle for independence from the colonialist rule of Great Britain.

Brought up in the coastal city of Porbandar, in the Indian state of Gujarat, Gandhi was the son of the city’s chief minister. His deeply religious mother was a devoted practitioner of Vaishnavism, a religion that worships the Hindu god Vishnu. As a result of these parental influences Gandhi’s childhood was filled with self-discipline and nonviolence – characteristics that in adulthood went on to influence his political advocacy of peaceful resistance.

After attending law school in London and being called to the English bar in 1891, Gandhi returned to India and set up a practice in Bombay. The business wasn’t successful, however, and he eventually took a job as a lawyer in South Africa where he subsequently stayed for over 20 years.

Gandhi was deeply shocked by the discrimination he experienced in South Africa. On one occasion, when a white magistrate asked him to remove his turban, Gandhi refused to do so and left the courtroom indignantly. This was but one of his many encounters with racism in the country. Another occurred while taking a train to Pretoria when an official ejected him from the first-class compartment and pushed him out onto on the platform. This experience served as a turning point for Gandhi, and he decided to respond to it through practising non-violence. He soon began teaching the concept of Satyagraha (“truth and firmness”) and promoting the use of passive resistance and non-consent against the authorities.

Gandhi was deeply shocked by the discrimination he experienced in South Africa. On one occasion, when a white magistrate asked him to remove his turban, Gandhi refused to do so and left the courtroom indignantly. This was but one of his many encounters with racism in the country. Another occurred while taking a train to Pretoria when an official ejected him from the first-class compartment and pushed him out onto on the platform. This experience served as a turning point for Gandhi, and he decided to respond to it through practising non-violence. He soon began teaching the concept of Satyagraha (“truth and firmness”) and promoting the use of passive resistance and non-consent against the authorities.

During the 1899-1902 Boer War, which was fought over the British Empire’s influence in South Africa, Gandhi formed a group of stretcher-bearers who were known as the Natal Indian Ambulance Corps. In all he raised 1100 Indian volunteers to support the British troops in this way against the Boers. Far from finding that the British were grateful for his help, however, the post-war period saw the passing of still further discriminating laws against South African Indian people.

Passive resistance

When South African Indians were forced to submit to the so-called Asiatic Registration Act of 1906, which required them to be fingerprinted and to carry registration documents with them at all times, Gandhi organized a campaign of civil disobedience that saw the authorities jail thousands of people, with many shot dead.

When South African Indians were forced to submit to the so-called Asiatic Registration Act of 1906, which required them to be fingerprinted and to carry registration documents with them at all times, Gandhi organized a campaign of civil disobedience that saw the authorities jail thousands of people, with many shot dead.

The British government gradually began to realize that the political situation in South Africa was at risk of developing into a civil war. This eventually resulted in a compromise being negotiated. Indian marriages became recognized, for example, and an annual tax on Indians was repealed.

A global figure

Gandhi eventually left South Africa in 1915 and returned to India. Despite having supported the British in World War I, he remained critical of the colonial authorities whom he felt were unjust.

Gandhi eventually left South Africa in 1915 and returned to India. Despite having supported the British in World War I, he remained critical of the colonial authorities whom he felt were unjust.

In 1919 the Rowlatt Act was passed in India, which gave the British colonial authorities emergency powers to suppress activities deemed to be subversive. Gandhi immediately launched a campaign of passive resistance. However, he quickly ended it after violence broke out that resulted in 379 deaths and over 1000 wounded.

By 1920 Gandhi had become leader of the Indian National Congress party. Now a prominent global figure, he openly supported the goal of India achieving economic and political independence from Britain. Gandhi’s charisma and ascetic lifestyle was based on peacefulness, prayer, fasting and meditation, and his numbers of followers were growing larger by the day. His efforts gradually turned the Indian independence movement into a truly national campaign. Little by little, British influence in India was beginning to be reduced.

In 1931, after the British authorities made some concessions, Gandhi suspended the civil disobedience movement and agreed to represent the National Congress party at the so-called Round Table Conferences in London. His hope was that the situation in India might improve through negotiation with the British rulers. But this was not to be the case. In fact, Gandhi was now even experiencing backstabbing from within his own party, as some of his colleagues had grown frustrated with his peaceful methods and were accusing him of having not achieved anything.

Following his return to India from London after a second Round Table Conference, Gandhi once again started a campaign of civil resistance. This resulted in him being arrested and, not for the first time, jailed. In protest against his imprisonment and the British government’s treatment of India’s poorer classes, Ghandi subsequently began a series of hunger strikes.

Following his return to India from London after a second Round Table Conference, Gandhi once again started a campaign of civil resistance. This resulted in him being arrested and, not for the first time, jailed. In protest against his imprisonment and the British government’s treatment of India’s poorer classes, Ghandi subsequently began a series of hunger strikes.

In 1934 Gandhi resigned his membership of the Congress party and began to concentrate his efforts on working in rural areas. But his political actions intensified when World War II broke out, and he opposed India’s participation on the grounds that he could not support a war for democratic freedom while such rights were still being denied to the Indian people themselves.

After the war, when the Labour Party took power in Britain, serious negotiations about India’s independence finally got underway. Britain subsequently granted India its independence on 15 August 1947. In doing so however it divided the country into two parts: India and Pakistan. Although Gandhi did not fully support this partitioning he still went along with it as he hoped that Hindus and Muslims could, in future, eventually achieve peace together.

Assassination and legacy

On 30 January 1948, while on his way to a prayer meeting, Gandhi was shot to death at point-blank range by Nathuram Godse, a Hindu fanatic who was enraged by his attempts to negotiate with Muslim leaders.

On 30 January 1948, while on his way to a prayer meeting, Gandhi was shot to death at point-blank range by Nathuram Godse, a Hindu fanatic who was enraged by his attempts to negotiate with Muslim leaders.

Gandhi’s death was mourned throughout India, with around 2 million people taking part in a five-mile long funeral procession. Cremated on the banks of the Jumna river, Gandhi left behind countless millions of devoted followers.

Despite all that had happened, Britain didn’t show proper respect for Gandhi until decades after his death. On 14 March, 2015, over 67 years after his assassination, a statue was erected in London’s Parliament Square to honour the centennial anniversary of his return to India in 1915, the year that essentially marked the beginning of his struggle for the country’s independence from British rule.

A towering figure in both Indian and global political history, Gandhi has influenced numerous other campaigners, leaders, and political movements worldwide. Of everything that has been written about him, perhaps the physicist Albert Einstein put it best:

| “Mahatma Gandhi’s life achievement stands unique in political history. He has invented a completely new and humane means for the liberation war of an oppressed country, and practised it with greatest energy and devotion. The moral influence he had on the consciously thinking human being of the entire civilised world will probably be much more lasting than it seems in our time with its overestimation of brutal violent forces. Because lasting will only be the work of such statesmen who wake up and strengthen the moral power of their people through their example and educational works. We may all be happy and grateful that destiny gifted us with such an enlightened contemporary, a role model for the generations to come. Generations to come will scarce believe that such a one as this walked the earth in flesh and blood.” |