- Have any questions? Contact us!

- info@dr-rath-foundation.org

US Coastal Dwellers Low In Omega-3s Despite Affluence & Access To Fish, Survey Finds

October 10, 2019

Bad News for Pharma: Yet Another Study Suggests Healthier Diets May Reduce Depression

October 11, 2019Working At The Linus Pauling Institute

I remember the day in early 1990 when I drove into Palo Alto on Page Mill Road. I was full of ideas and plans to confirm the vitamin C-heart disease connection at the experimental level. At 440 Page Mill Road I stopped my car. This was the Linus Pauling Institute in California, where I had been several times before, meeting with Linus during my student days. But this time it was different. Here would be my new workplace, and one of the greatest rides in the history of medical science was waiting for me. I was excited.

Besides Linus, no one knew about the forthcoming scientific earthquake and the sequence of explosions that would detonate at this rather uneventful institute. In order to cover the true nature of this discovery and to protect it from curious colleagues, Linus and I agreed on code language about the project. Even the lecture I had given in early January to the employees of the Pauling Institute had been on the lipoprotein(a) work alone – without mentioning any connection to vitamin C, which, of course, was the truly exciting part of it.

The next morning Linus and I met with the President of the institute. Linus addressed him directly: “I want everyone at the institute to know that Matthias is my personal protégé.” Later I realized that the two-time Nobel Laureate had made this statement not only based on his friendship and common scientific interests with me, but also because he was aware that his institute had become a minefield.

The Pauling Institute had been in existence for two decades but had lost its profile of being a vitamin research institute. Only one out of ten researchers even worked on vitamin C, and millions of dollars in donations from around the world were wasted on research not even remotely related to documenting the health benefits of vitamins. Linus’ last book ‘How To Live Longer And Feel Better’ listed two hundred supporting references, but less than a handful came from his own institute! Clearly, the Nobel Laureate had entrusted his institute into the hands of people who were shy of leading the battle for the acceptance of vitamins for health. Tens of thousands of readers of Linus Pauling’s books connected his name with ongoing vitamin research, but the administration of his institute was ashamed of controversies and taking up the good fight for natural health.

In this situation, Linus, at the age of 90, had obviously realized that this could be his last opportunity to find a young and enthusiastic researcher to carry on his life’s work. However, the announcement that I was his protégé could not have been more threatening to the existing leadership of the institute. I would soon feel the consequences of this. Instead of getting a decent workplace with a desk and chair, I was allocated the corner seat in the windowless storage area of the institute. My request to the institute’s administration for a research assistant who could help in the laboratory was met with the argument that the institute didn’t have the money.

Not willing to give up, I trained the janitor to run the electrophoresis experiments in the laboratory so I could concentrate on elaborating the details of the medical breakthrough. Weeks, perhaps months, were lost and it was not until a year later that I finally got a qualified research assistant.

Key experiments for the medical breakthrough

I had already made the principal discovery of the vitamin C deficiency-lipoprotein(a) connection back in 1987. Now the door was wide open for the scientific proof. I set up a study with guinea pigs, an animal that shares the same genetic defect as human beings. These animals cannot produce their own vitamin C. The experiment was straightforward. My theory was that guinea pigs develop arteriosclerotic deposits once they are put on a vitamin C deficient diet. Moreover, by analyzing the deposits in the animals’ artery walls we would find the sticky lipoprotein(a) fat molecules.

The significance of this key experiment for the health and lives of millions of people could not be underestimated. This experiment would enable the conclusion that a similar mechanism takes place in the human body. The lack of vitamin C would weaken the blood vessel walls and subsequently lipoprotein(a), cholesterol and other risk factors in the blood would be deposited in the artery walls to mend them. That would prove that fatty deposits in the arteries are not a coincidence or just ‘fate’, and that cardiovascular diseases develop as an inevitable response of the body to repair blood vessel walls that are weakened by vitamin deficiency.

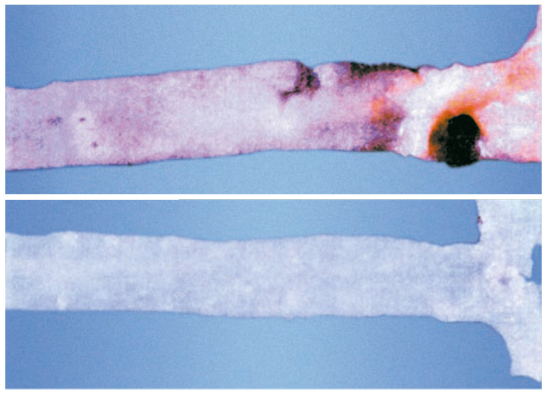

Top image: Guinea pigs receiving too little vitamin C develop cardiovascular disease.

Bottom image: Guinea pigs receiving optimum vitamin C have clean arteries.

The moment of truth

The key experiment was carried out over five weeks, one of the longest five weeks of my life. Of course, animal experiments have to be kept to an absolute minimum. But since this experiment would have meaning for the health and lives of millions of people, it had been approved by the animal care committee of the institute. I still remember the day when the experiment was over, and I looked at the artery walls of the guinea pigs under the microscope. The guinea pigs receiving vitamin C at a daily dose comparable to the human recommended daily allowance (RDA) had developed the same deposits in their artery walls that cause heart attacks and strokes in human beings. However, those animals that received the equivalent of two teaspoonfuls of vitamin C per day, comparable to human body weight, had maintained clean arteries. Most importantly, this striking difference was not obtained by adding cholesterol or fat to the animals’ diet, but by omitting one single factor from it: vitamin C.

That day I felt like Columbus must have felt at the first sight of land in 1492, after years of struggle and overcoming adversities. I went to Dorothy Munroe, Linus Pauling’s secretary, and asked her where I could reach him to share the exciting news. She noticed my excitement and said: ”Go right in, he is in his office.” I didn’t even close the door behind me, and shouted: “Linus, you’ve got to come and see this!”

He had been dictating letters and correspondence in his typical posture, half lying in his chair with his feet on the desk. His black beret was drawn deep over his eyes, in order to dim the neon light of his office. He jumped up, adjusted his beret, and walked with me to the room where the guinea pig arteries had been placed under the microscope. The results left no doubt: an optimal amount of vitamin C was the solution to the cardiovascular epidemic.

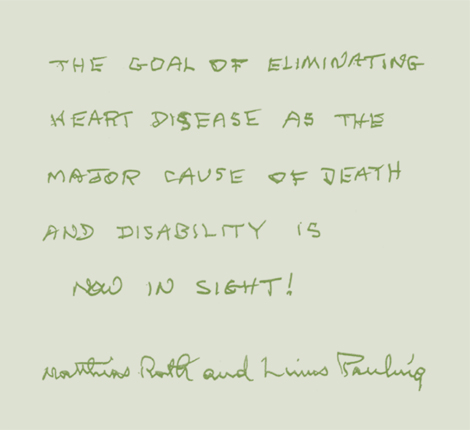

Final paragraph from the historic Rath-Pauling Manifesto, ‘Call for an International Effort to Abolish Heart Disease’, issued in April 1992.

After looking through the microscope for a few minutes Linus rose, turned around, and beamed at me: “I am happy as a clam,” he said. He took me by the arm, and we went to his office to immediately discuss the next steps, as well as the implications for human health.

That evening, when I drove home, I knew that medicine would never again be the same. Thoughts were appearing like flashes in my mind, and a breathtaking perspective was opening up. I saw people around the world embracing this discovery, and researchers tuning in to further confirm it at all levels. I imagined the morning news opening up with the headline: ‘Heart disease close to eradication’. I could see a new research institute rising into the sky. How could I know that the fight for the acceptance of this simple truth had just began, and that years of fierce battles lay ahead of me.