- Have any questions? Contact us!

- info@dr-rath-foundation.org

Ten Reasons Why Preventive Healthcare And Eliminating Diseases Are Not Possible Under the Brussels EU

June 29, 2017

A Fresh Approach: The Importance Of Clean Water For The Human Body Cells

July 13, 2017Brussels EU Commission President Jean-Claude Juncker Denounces EU Parliament As “Ridiculous”

By Zinneke [CC BY-SA 3.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0)], from Wikimedia Commons

It’s not very often that I find myself agreeing with the Brussels EU Commission President, Jean-Claude Juncker. However, this week was one of those extremely rare occasions when I found myself in complete agreement with him. Speaking at a session of the EU Parliament that was reviewing the six-month European Council presidency of Malta, the construct’s smallest member state, Juncker observed that only around 30 of the Parliament’s 751 members were present and openly denounced the institution as “ridiculous.” Frankly, if challenged to think of a word that more perfectly summarizes the farcical nature of this Parliament, I could hardly have selected a better one myself.

Despite angry protestations from Antonio Tajani, the Parliament’s President (in all, the bloated Brussels EU bureaucracy has a total of 7 presidents, none of whom are elected by citizens at the European level), Juncker bravely persisted in his attack. Dismissing Tajani’s rebukes, he said he would “never again attend a meeting of this kind.” Seemingly, therefore, with the talks on Britain’s imminent departure from the Brussels EU now fully underway, the fallout among the bloc’s senior officials is beginning to spill over into the public arena.

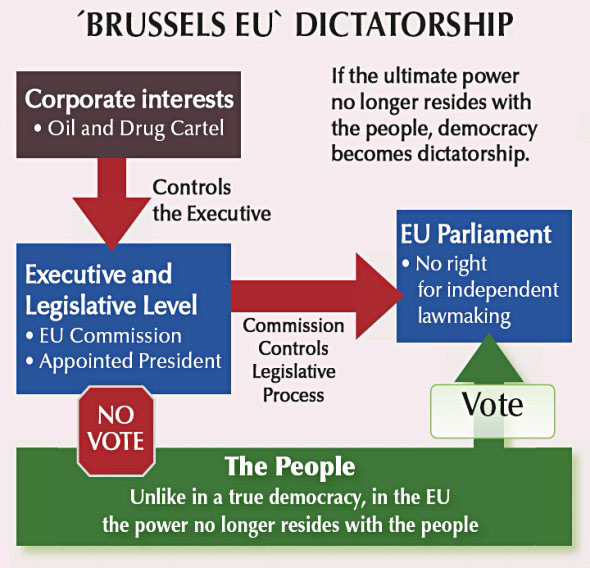

The Brussels EU is NOT a democracy

At least theoretically, the Brussels EU Commission is supposed to be under the control of the Brussels EU Parliament. While this was grudgingly acknowledged by Juncker in his indignant exchanges with Tajani, the reality behind the scenes is very different. The real political power in Europe lies with the Commission and its multinational corporate masters. Far from being under the control of the Parliament, the Commission functions as the de facto executive body of Europe. The Parliament, on the other hand, has no right for independent lawmaking. Instead, it exists as a mere rubber-stamping chamber, with the laws of Europe simply being handed down to it by the Commission for approval.

Consisting of 28 members, known as its “commissioners”, the Commission controls the legislative process in Europe. However, none of these 28 people ever stand in a proper democratic election. Instead, every single one of them – including even the president of the Commission, Jean-Claude Juncker himself – are simply appointed to their roles. Worse still, corporate and other special interests are invariably highly influential in the appointing of all senior Brussels EU officials. In 2009, for example, Herman Van Rompuy was selected for the role of President of the Brussels EU Council following an elite dinner meeting with the secretive Bilderberg Group.

The Brussels EU is incapable of reform

Signed by Brussels EU member state leaders on 13 December, 2007, 96 percent of the text of the Lisbon Treaty was taken from the ‘EU Constitution’ that had previously been rejected by voters in France and the Netherlands in 2005.

Had the Brussels EU been genuinely interested in reform, it could have implemented a proper democratic approach years ago. Time and again, however, when faced with evidence that it doesn’t have the support of European citizens, the construct has proven itself utterly incapable of change. A classic example of this occurred following the rejection of the so-called ‘EU Constitution’ by France and the Netherlands in national referendums held in 2005. Intended to be an ‘Enabling Act’ for the Brussels EU to consolidate its power over Europe, the text of this Constitution created the basis for a system of European government that is fundamentally undemocratic.

In any real democracy, the rejection of a constitution through referendums would have been taken as a clear lack of support from citizens. Instead, however, in a typically undemocratic Brussels EU response, 96 percent of the text was simply repackaged and renamed as the Lisbon Treaty.

The only European country that was subsequently given a vote on the new so-called Lisbon Treaty was Ireland – and even this was merely because it was required to do so under its own national constitution. So in June 2008 it was the turn of the people of Ireland to deliver a resounding shock to the Brussels EU by voting ‘No’. But the Brussels EU once again refused to accept this and Ireland was asked to vote again.

Crucially, however, in preparation for its second vote on the Treaty, Ireland’s guidelines on media impartiality were altered in such a way that commercial radio and television stations did not have to give equal airtime to both sides of the debate. As a result, the Irish people voted ‘Yes’ in the revote in October 2009 and the Lisbon Treaty passed into Brussels EU law 2 months later. So much for European democracy, then.

Earlier this year, Jean-Claude Juncker admitted that Britain’s decision to quit the Brussels EU was a failure and a tragedy for the construct. Given the bloc’s ongoing refusal to engage in any meaningful democratic reform, the fact that Juncker and his colleagues found Brexit at all surprising is arguably one of the most ridiculous things of all.