- Have any questions? Contact us!

- info@dr-rath-foundation.org

Promoting Old Drugs For Dangerous New Uses: Study Claims Calcium Channel Blockers Stop Spread Of Cancer

January 19, 2017

Micronutrient synergy approach suppresses growth of colon cancer

January 26, 2017They Still Dance On The Graves Of The Auschwitz Survivors

Heavy rain can really set the mood when you visit somewhere. Hollywood has known this for years, and movie makers have used it to great effect ever since. But with nature writing the screenplay today, such weather is more than fitting at my location – the remains of one of the biggest crimes in humankind’s history. I am visiting Oświęcim, a small town in rural Poland. This place might be better known to you by the German name that the oppressors used for it during their brief, fatal time here in the late 1930s and early 1940s: Auschwitz.

A day in the life of an Auschwitz tourist

No matter where you come from, a visit to the Auschwitz Concentration Camp follows the same script. You will arrive at the Auschwitz I site in your bus, gather at the entrance, and be allocated a guide to lead you through the museum. Your camera and/or your smartphone will remain in your hand throughout the day. The first photo you take will be one of the most recognizable. You will stop at the infamous entrance, with its gravely sarcastic “Arbeit macht frei” message (which means “work makes you free”), and you will take a selfie or let a friend snap a photo of you. Everybody at home will recognize where you are.

The guide will walk you through the older, brick-built buildings of this World Heritage Site and show you all the things the Nazis didn’t burn when they fled the place – carpets made of human hair; mountains of shoes; empty cans of Zyklon B poison; and the countless suitcases belonging to the people who were killed. You will feel the frightening karma of this place. Especially in the prison cells and the rooms containing the ovens. It’s impossible to believe that a human being would have been able to fit into those small cells. Unbelievable that humans did this to other humans.

The poison gas Zyklon B (left image) was manufactured by IG Farben and not only used in Auschwitz. Suitcases belonging to people who were killed (right image) can be seen today in Auschwitz I.

Next, you will drive to the second, larger camp, Auschwitz II – Birkenau. Here, you will recognize the scenes from Schindler’s List. Maybe you imagine a red raincoat in the distance, among the clothes of those killed in this horrific place. You will certainly see where the trains arrived, and where the IG Farben doctors assessed each new arrival. Were they able to work? Or were they useless and should they be killed?

You will walk from the site where the trains arrive to what is left of the large gas chambers. You will not feel the rain. You are here in your multi-layered jacket, made of synthetic Bayer plastic fibers. Maybe you will remember that the poor people who were forced to live here had nothing like that. Just a bunch of rags to wear, and a barrack where the rain poured through.

On your way back to the bus, the guide will show you one of the barracks that are still standing today. You will feel the darkness, even during the day, and sense how cold and windy it is. Imagine the snow-filled days of the winter in 1942. How did people survive? Perhaps the guide will tell you how many people used to live in one of these barracks, and how many barracks there were in the days when IG Auschwitz was still in business. They might even tell you a story about one of the survivors.

Did you ever think about what those thousands of people were doing in this awful place? And that there were millions of individuals who lived, worked, survived, or died here? Each individual had his or her own family members and friends. We should really try to imagine the fate of each individual behind the familiar story of over 1 million anonymous victims.

The men who still hide in the darkness, and dance on the graves of the survivors

On your second visit, you should go on a little detour. Leave behind the busloads of tourists that walk through the official concentration camp. Leave behind those who only see the officially authorized picture, the one painted by the industry of remembrance. If you look carefully, you can still see the remains of the driving force behind this work/death machine. Barely anyone notices it, and no official guide will mention it. But parts of IG Auschwitz, the colossal industrial complex of IG Farben, are still there.

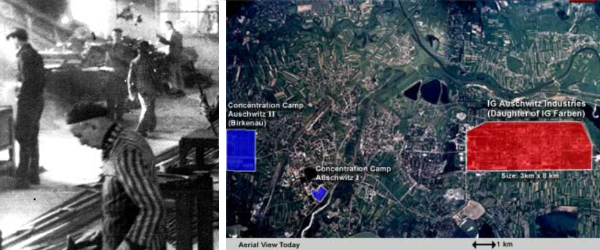

Inmates of the Auschwitz concentration camp were forced to work in the plant (left). The size of the IG Auschwitz plant (red area) was larger than all Auschwitz concentration camps (blue area) taken together.

There are concrete buildings that continue to be used today. You can follow the industrial pipes that were in use on the first day of business at the factories and are still operational now. Drive around the borders of the complex and see how long it takes you. See how huge it really is. All hidden from the public eye. Hidden from the Instagram photos that share scenes of the Auschwitz I entrance, or the Facebook post from the site where the trains arrived in Auschwitz II. It is woven into a typical Polish industrial area that you would normally only enter when you have business to conduct there. It is still very much visible though. That is, if you look close enough, if you look behind the official picture that you are being told to see.

You are taught to believe that a bunch of lunatics imprisoned innocent men, women and children, and forced them to work until their deaths. The reality is much more frightening: IG Auschwitz and the Auschwitz concentration camp were planned by businessmen who were trying to make as much profit as possible using the cheapest labor resources available. Ten years ago, for the work it has done in bringing this story to the attention of the world, the Dr. Rath Health Foundation received the “Relay of Life and Remembrance” from the survivors of Auschwitz.

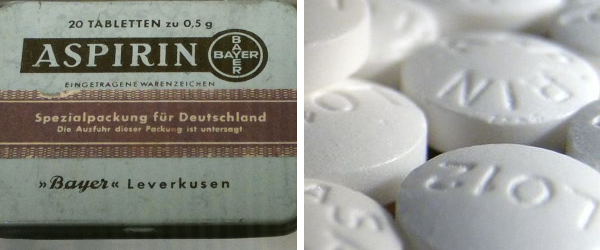

Aspirin in the IG Farben era (left image) and today (right image). This drug stimulated the sales of IG Farben. Today, it still boosts profits for Bayer. Left image: By ANKAWÜ (Own work) [CC BY-SA 3.0], via Wikimedia Commons | Right image: By 14 Mostafa&zeyad (Own work) [CC BY-SA 4.0], via Wikimedia Commons

But the business heritage of the petrochemical and pharmaceutical company IG Farben marches on. Bayer, Hoechst (now part of Sanofi-Aventis), and BASF were built from IG Farben assets, sold IG Farben pharmaceuticals and chemicals, shared the same executives and, most importantly, retain the same business model. Today, however, they operate on a much larger scale than ever before.

In 1942, during World War II, IG Farben had a turnover equivalent to $13.7 billion in today’s money. In 2015, the sales of Bayer alone reached $49.8 billion.

One could argue that not much has changed.