They called themselves ‘Vitamins Inc’ and conspired in one of the biggest cartels in recent history. The story behind the vitamin cartel of the 1990s, one of the most harmful and far-reaching cartels ever, provides a graphic example of the unscrupulous business ethics of the pharmaceutical industry. An international cartel controlling the production of vitamin raw materials, its actions did not only affect the prices of nutritional supplements, but also those of products produced by big food multinationals such as Kellogg’s, Coca Cola and Nestlé, which similarly include vitamins as ingredients.

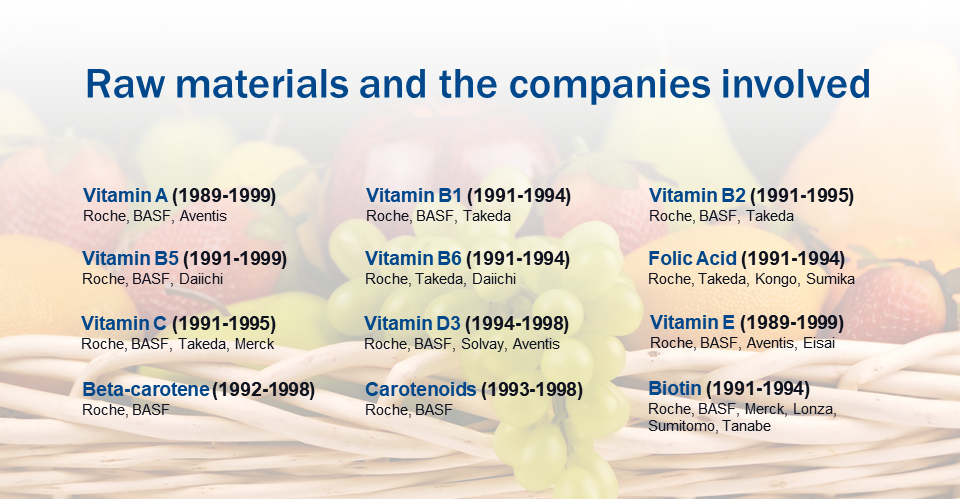

13 companies were active in the vitamin cartel. Roche (Switzerland), BASF (Germany), and Takeda (Japan) were some of the key players.

Looking back

In the 1990s, the market for vitamin raw materials was controlled by a small number of pharmaceutical companies. Since demand for these raw materials was high, the market essentially provided an open invitation to form a criminal cartel.

Roche was the industry leader, with a history dating back to the 1930s. Over the years, only a few rivals had been able to enter the market. As a result, during the 1970s, Roche had already been fined for monopolistic behavior in relation to its vitamin division. But it took almost another 20 years before a medical breakthrough sparked new interest in nutritional supplements.

After Dr. Matthias Rath published his first scientific papers about the role of vitamin deficiency in heart disease, he and Roche had established contact. However, seeing the potential for its vitamin division to increase global demand for vitamin raw materials and establish a multibillion-dollar market, the company decided to proceed without Dr. Rath. Instead, it chose to contact its next biggest rival—German multinational BASF. With a rich history of illegal behavior behind it, Roche was the perfect ringleader for a criminal cartel.

The companies involved in the cartel met in Switzerland. There, prices were fixed, and output determined. The result was that while the cartel’s production costs remained constant or even fell, the prices it charged increased. The cartel’s members profited enormously from this illegal price-fixing. For example, Roche had revenues of 3.3 billion dollars in the US alone while the cartel was operating.

But the disproportion between production costs and profits had not gone unnoticed by new entrants to the vitamin raw materials market. Other companies—particularly in China—started to invest heavily and were able to offer their own raw materials at a much lower price. With profits beginning to decline, some members of the vitamin cartel started to question their criminal pact. This marked the beginning of the end for the cartel.

The end of the cartel

In 1999, French pharmaceutical company Rhône-Poulenc opened up about the vitamin cartel in order to escape potentially punitive fines. Investigations were launched by regulators in the US and Europe that eventually resulted in the end of the cartel.

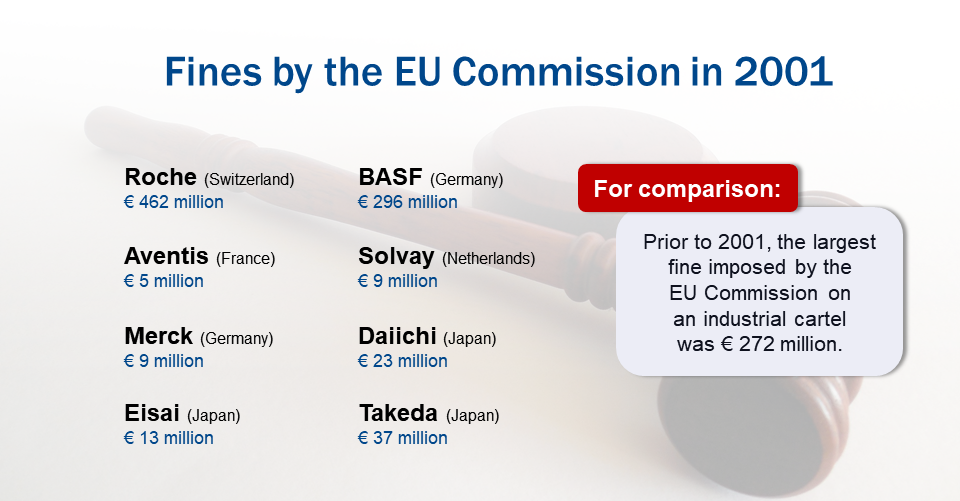

Roche received fines in the US and Europe totaling almost 1 billion dollars. It also had to pay an additional 1 billion dollars to settle class action lawsuits. BASF, too, received fines on both sides of the Atlantic. In all, a total of eight companies were fined. The vitamin cartel was the biggest industrial cartel discovered up until that time. Writing in October 1999, the New York Times commented that: “Not since the reign of I. G. Farben, the German chemical giant that operated as a state-sponsored conglomerate in the 1930s and 1940s, has an international cartel so effectively and systematically manipulated a world market.“

As a result of its involvement in the vitamin cartel, the heavy fines it received, and the destruction of its reputation, Roche was eventually forced to sell its vitamin raw material division to DSM, a multinational headquartered in the Netherlands.

Looking ahead

Today the market for producing vitamin raw materials is a profitable business. New discoveries in vitamin research are increasing the public’s interest and stimulating the demand for micronutrient supplements. The demand for vitamin C products alone has been estimated to be growing by over 5 percent per year.

New companies are entering the nutritional supplements market and using social networks as a tool to rapidly grow their market share. But vitamin raw materials are not only found in supplements; increasingly, our everyday food is fortified with vitamins as well.

However, the story of the vitamin cartel teaches us that we have to remain cautious. For example, only a fraction of the nutritional supplements on the market today are of high quality. Research shows that use of inferior products can carry serious risks for consumers.

The Dr. Rath Health Foundation continues to keep a watchful eye on the latest developments in this area and remains the number one source for science-based natural health information. If you have not done so already, we encourage you to subscribe to our newsletter and follow us on Twitter and Facebook to keep yourself up-to-date. In the field of natural health, as with much else in life, information is power.