- Have any questions? Contact us!

- info@dr-rath-foundation.org

Higher Doses Of Omega-3 Supplements May Be Needed For Averting Cognitive Decline

July 24, 2020

Low Plasma Vitamin D Level Associated With Increased Risk Of Coronavirus Infection

July 31, 2020New Study Provides Evidence Showing Vitamin C Deficiency Is Common Worldwide

A new review of the available scientific evidence suggests that vitamin C deficiency is common worldwide. Published in the journal Nutrients, it examines global research on vitamin C status and the prevalence of low and deficient levels among populations. Contrary to often heard claims that vitamin C deficiency is rare, the researchers found it is common in low- and middle-income countries and not uncommon in high-income ones. Recognizing what they describe as “potential protective effects” of vitamin C against cardiovascular diseases, cancer, cataracts, and multiple infectious diseases, the researchers conclude that improving vitamin C intake may prove to be a cheap and effective public health intervention.

The paper describes how vitamin C has to be consumed on a regular basis in order to prevent deficiency. It also notes that, bearing in mind growing evidence that higher intakes have beneficial effects on health, in recent years many regulatory authorities have increased their recommended daily allowances (RDAs). Despite this, the paper suggests that low and deficient levels among populations would still appear to be widespread.

Vitamin C deficiency in high-income countries

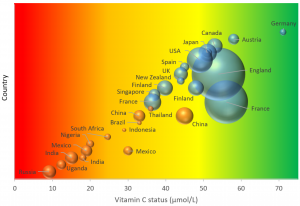

Global adult vitamin C status. The area of the bubble represents the size of the study. Blue bubbles represent high-income countries; orange bubbles represent low- and middle-income countries. Vitamin C status cutoffs: red—deficient; orange—hypovitaminosis C; yellow-inadequate; green—adequate. / Source: mdpi.com

Many doctors incorrectly believe that vitamin deficiencies are rare in high-income countries. Such beliefs are hardly surprising, of course, as they have been drummed into medical students for decades now. While it is true that some studies broadly support this position, the findings of other papers differ quite widely. Studies cited in the Nutrients paper show that vitamin C deficiency is not uncommon in high-income countries.

In one example, a study carried out in Glasgow, Scotland, in 1992 examined people aged between 25 and 74 years of age. It found that 26 percent of men and 14 percent of women were deficient in vitamin C. Notably, therefore, given the proven link between vitamin C deficiency and cardiovascular disease, people in Glasgow are known to have particularly high rates of heart attack.

In the United States, National Health and Nutrition Examination Surveys have been reporting vitamin C status data for nearly four decades now. The most recent survey was carried out between 2003 and 2004 and indicated that 10 percent of men and 6.9 percent of women were deficient in vitamin C.

High rates of vitamin C deficiency have also been uncovered in wealthier Asian countries. In Singapore, for example, 17 percent of men and 6 percent of women have been shown to be deficient. As we shall see next, however, among low- and middle-income countries vitamin C deficiency is even more widespread.

Vitamin C deficiency in low- and middle-income countries

High rates of vitamin C deficiency have been found among adults aged over 60 in India / Source: Adam Jones from Kelowna, BC, Canada (CC BY-SA)

Evidence examined in the Nutrients paper suggests that high proportions of people in Central and South America have low levels of vitamin C. Studies in Mexican women have found that up to 39 percent lack proper levels, for example, while a study of elderly people in Ecuador found 60 percent of men and 33 percent of women were deficient. Similarly, a study looking at 117 pregnant women admitted to hospital in Sao Paulo, Brazil, found 31 percent had insufficient levels.

Research has also uncovered widespread vitamin C deficiency in Africa. A study assessing vitamin C concentrations in 285 elderly people in South Africa found that 84 percent of men and 62 percent of women had low levels. In Nigeria, a study of 400 women attending an antenatal clinic found an astonishing 80 percent had insufficient levels. Similar findings have been made in Uganda, where research into pre-eclampsia in a hospital in Kampala found 70 percent of women were deficient. Perhaps not surprisingly, therefore, the Nutrients paper notes that clinical outbreaks of scurvy still occur in Africa.

High rates of vitamin C deficiency have similarly been found in India. In a study of adults aged over 60, deficiency was observed in 74 percent of people in North India and 46 percent in South India. Research in Russia has found 90 percent of adult men have low levels of the nutrient, with 79 percent having outright deficiency. In Afghanistan severe outbreaks of scurvy have been noted in the winter months.

How much vitamin C do we need?

In his book, ‘Why Animals Don’t Get Heart Attacks…But People Do’, Dr. Rath recommends a daily vitamin C intake of between 600–3000 mg

The Nutrients paper describes how recommended dietary intakes of vitamin C vary significantly between countries, with the advised daily amounts ranging from 40 mg to around 200 mg. Clearly, the lowest of these recommendations would appear to be designed merely to prevent outright deficiency, rather than to optimize health. This raises important questions regarding how we should define deficiency, and how much vitamin C we need for optimum health.

The Nutrients paper suggests that vitamin C intakes of 100–200 mg per day will maintain blood concentrations at “adequate to saturating status”, which it defines as a level of between 50–75 µmol/L (micromoles per liter). Hypovitaminosis, or low vitamin C, is defined as a level less than 23 µmol/L, with deficiency defined as less than 11 µmol/L. But for optimum health, including the prevention of cardiovascular disease and other health problems, even an intake of 200 mg per day is insufficient.

In his book, ‘Why Animals Don’t Get Heart Attacks…But People Do’, Dr. Rath recommends a daily vitamin C intake of between 600–3000 mg. He furthermore states that patients and people with special nutritional needs may require two or three times this much and advises that vitamin C should be taken as part of a synergistically designed combination of vitamins, minerals, amino acids, and trace elements. These recommendations are built on his more than thirty years of research examining the health benefits of micronutrients in fighting a multitude of diseases.

In their conclusion to the Nutrients paper the authors advise that clinicians should remain vigilant to vitamin C deficiency as a cause or contributing factor to common health problems. They also recognize the value of supplementation and describe how research has indicated that the bioavailability of vitamin C from supplements is comparable to that from fruit and vegetables. Their paper should be essential reading for any doctor who still believes that vitamin C deficiency is rare or that supplements have no place in the prevention of diseases.